I agree, ax. I particularly feel that I missed out on the combination of logic and rhetoric in my school and undergraduate education. I did study logic as part of my comp. science courses in school, but never saw the connection to logic and rhetoric as a thinking and writing tool.axordil wrote:It's less the particular languages than the pedagogy they represented that I pine for: logic, grammar, rhetoric. Those are the areas that define the ability to be a thinking member of society.

Classics in school and education in general

'You just said "your getting shorter": you've obviously been drinking too much ent-draught and not enough Prim's.' - Jude

- Túrin Turambar

- Posts: 6157

- Joined: Sat Dec 03, 2005 9:37 am

- Location: Melbourne, Victoria

I’m bumping this thread because another interesting discussion has broken out over here about the status of the humanities in higher education. Some people are suggesting that, more and more, areas of study like literature and philosophy are giving way in universities to the professions, social sciences and hard sciences.

The professions and social sciences are certainly booming at the moment. I know from personal experience that supply of law graduates has well outstripped demand. I’d question whether the physical sciences are doing quite as well.

This has led to a debate about the purpose of universities and higher education in general, which has been heightened of late by the news of the funding cuts in Britain’s higher education sector. Here’s a couple of articles on the topic that I found very interesting, both in a response to a series of blog posts by Dr Mark Banisch, a sociologist at Griffith University in Queensland (my own esteemed institution of higher learning). Here’s one by blogger Ken Parish:

That said, I do think that some exposure to the classics and philosophy and the like is a great thing. I understand law, politics and economics much better than I otherwise would because I’ve read and, more importantly, been taught to understand works by writers like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. But I don’t believe that everybody would benefit from it, I don’t think that it must be a necessary part of every degree, and I’d oppose it if it was either so dumbed down as to be useless or (in my personal experience) taught in such an arcane and politically-loaded fashion as to be almost a parody of itself. And there are, after all, excellent lawyers and economists who’ve never read Hobbes or Locke at all.

Here’s an extract from another post on the subject:

The professions and social sciences are certainly booming at the moment. I know from personal experience that supply of law graduates has well outstripped demand. I’d question whether the physical sciences are doing quite as well.

This has led to a debate about the purpose of universities and higher education in general, which has been heightened of late by the news of the funding cuts in Britain’s higher education sector. Here’s a couple of articles on the topic that I found very interesting, both in a response to a series of blog posts by Dr Mark Banisch, a sociologist at Griffith University in Queensland (my own esteemed institution of higher learning). Here’s one by blogger Ken Parish:

Unlike Parish or Goldworthy, I’m not persuaded that there is all that much of an ‘inherent value’ to a liberal tertiary education worthy of its investment in time and money. I believe that being well-read and open-minded is a virtue, and being able to read and think critically is a skill, and having an interest in broad knowledge is a great thing, but I’m not convinced that any of those things can be efficiently taught in a degree.Prompted by University of Queensland’s Graeme Turner, Mark Bahnisch has a pair of posts over at Larvatus Prodeo asking rhetorically whether the Humanities at Australian universities are dying. As Turner puts it:

ONCE, the humanities were fundamental to the idea of the university. Now science is at the core of the research mission of the Australian university, and professional training at the core of its teaching mission.

The humanities fight for space in each of these domains as the recognition of their importance declines.

In research the humanities receives a fair whack of funding from governments but very little from the corporate sector.

In terms of teaching (undergraduate enrolments), however, initial observation of DEEWR statistics doesn’t seem to bear out this pessimism, with 36,363 of 134,883 EFTSL (students) in 2009 falling under the “Society and Culture” category which includes the humanities and social sciences. That’s around 25% and it grew by a modest but respectable 5.1% from the previous year.

However the picture looks significantly less healthy when you strip out vocational/professional disciplines like law and psychology, and positively terminal if you focus on regional and even smaller metropolitan universities. Enrolments in the “soft” humanities and social sciences (English, history, political science, philosophy, religion, sociology, anthropology) are clearly under severe pressure.

The likely reasons are not hard to find. In the wake of the Dawkins revolution when teachers’ colleges and CAEs were transformed into universities and universal HECS fees were introduced, and with universities increasingly reliant on full fee-paying international students to stay afloat in the face of declining federal funding (until very recently), it was inevitable that students’ enrolment decisions would be dominated by public perceptions of the likely immediate vocational payoff from “investment” in a university degree. The soft humanities tend to do poorly on such perceptions. Academic Kerryn Goldsworthy (PC) observed:

Whenever I had to do the excruciating departmental shift at Melb U Open Day making nice with the Year Twelves, I would field the unending line of well-dressed fathers saying ‘But if she does English, what sort of job will it help her to get?’ with the standard answer that we would mould her into such a paragon of clear thinking, good written expression and broad understanding of human nature that employers in all sorts of fields would be falling over themselves to give her a job — at least if they had any brains, and who wants to work for a moron, right? Oh okay, I didn’t say that last bit.

Someone rather more cynically responded:

See, PC, you just didn’t know how to sell your English degree. With all that understanding of human nature you should have been able to size up those dads in a flash: our graduates become school teachers in country towns ’till they marry a fabulously rich farmer, or, our graduates become advertising executives and are all driving Porches before they’re 25 ….

Unfortunately these public perceptions of the commercial/vocational value of the soft humanities may be rather more formidable (or perhaps self-fulfilling) than this suggests. Recent UK research found:

Researchers compared the fortunes of around 80,000 people – graduates and those who left school or college after their A-levels – between 1997 and 2009.

It found a large earnings premium for women, regardless of their subject or degree grade. The report took account of student debts and higher tax returns.

Average woman with a degree in the arts, humanities or social sciences, as well as “combined” subjects, could expect to earn £25,000 more per year on average, said the report. This was equivalent to some £1m more over their working life.

But the report found the premium for a man could be less.

Men leaving school with A-levels earned an average of £35,000 a year, according to the study.

Those taking law, economics or management degrees could expect to earn an additional £30,000. The earnings premium for students taking combined degrees was £16,000 and those with science, technology, engineering and mathematics was £5,000.

But the study found the earnings premium for arts, humanities and social science degree – which can include fine art, music, drama, history, philosophy and theology – can be “effectively zero”.

My problem is that I agree with Kerryn Goldsworthy about the actual inherent value of a broad liberal tertiary education, so I’m hoping to focus some of the giant lateral thinking brains here at Troppo on the problems as I see them:

1. Is it feasible to get more modern undergraduate students exposed to and educated in the “soft” humanities and social sciences at least to some extent? How? Or must we accept that the times have irretrievably changed with mass higher education to a relentlessly narrow vocational focus?

2. In particular, how could this be done in smaller regional universities like the one where I teach?

3. Is there a useful point in considering compulsory “Foundation Studies” units in the soft humanities which ALL students (including the vast majority enrolled in narrowly vocational programs) would be obliged to study? Or would such units inevitably be so “dummed down” as to negate any real broad liberal educational value for the Great Unwashed Masses while diluting necessary rigor for the minority of serious humanities students?

That said, I do think that some exposure to the classics and philosophy and the like is a great thing. I understand law, politics and economics much better than I otherwise would because I’ve read and, more importantly, been taught to understand works by writers like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. But I don’t believe that everybody would benefit from it, I don’t think that it must be a necessary part of every degree, and I’d oppose it if it was either so dumbed down as to be useless or (in my personal experience) taught in such an arcane and politically-loaded fashion as to be almost a parody of itself. And there are, after all, excellent lawyers and economists who’ve never read Hobbes or Locke at all.

Here’s an extract from another post on the subject:

I don’t agree with point 2, but I think that everything else is spot-on.To that end, I am going to make a few suggestions for the humanities (hey, everyone else is) based on what I’ve seen. I’ve worked and studied in five universities in three countries, two of them considered among the most prestigious in the world. My scholarly interests also straddled the humanities, social sciences and sciences. I got to hang out in labs, play with MATLAB and translate obscure Roman law documents. I don’t have all (or perhaps even any) answers, but the comments I make are not borne of ignorance.

1. There are too many universities, and too many people going to university. Many universities are very mediocre, and many of the students who attend them are very mediocre. We seem to have forgotten how to tell people ‘no, you aren’t very clever, you shouldn’t go to university. You are, however, good with your hands. You should get an apprenticeship instead.’ There is, as Stanley Fish points out, nothing wrong with a trade school. Upgrading what were essentially trade schools and turning them into universities was always going to be a bad idea, and now we can’t afford them to boot. And let’s not forget that plumbers make a very good living.

2. Compulsory language requirements should be reinstated for the sciences, and compulsory science requirements should be reinstated for the humanities. It should not be possible to get through university — particularly in a high-powered professional discipline like law, medicine or engineering pleading ‘but I have a math allergy’ or ‘Latin is too hard’. If you have a math allergy, or Latin is too hard, you shouldn’t be studying engineering, medicine or law. End of.

3. Much higher research in the humanities — particularly at the mediocre universities, but even at some good ones — is, not to put too fine a point on it, bunk. It comes about because research imperatives (discussed very fully over at LP) that make sense in science do not work in the humanities (and even in some of the social sciences). As most of you know, I was offered a fully-funded scholarship place at Oxford to read for the DPhil in law. I am in the process of doing the final edits for my MPhil. What most of you won’t know is that — after considerable thought — I opted to decline the DPhil place. The principal reason for this decline? The scope of my research was so narrow as to be meaningless, and involved accepting intellectual constraints with which I disagree (more of this later), and which the university’s funders (both public and private) ought to find alarming.

4. Several commenters over at LP made the point that humanities academics need to stop with the pointless infighting and start supporting each other, so I will only make one behavioural recommendation directed at the humanities more generally. It is this: when you make falsifiable assertions, and some scientist or social scientist then proceeds to falsify them, accept the correction with good grace and move on. Empirically testable propositions are part of the magisterium of science and social science, and to the extent that humanities scholars make them, they have to accept that people from the other magisterium will make comment and draw conclusions. Many people on the LP thread were anxious to defend theory (although, interestingly, neither Mark nor the Australian scholar quoted, University of Queensland academic Graeme Turner, did so, recognizing instead that it is off-putting).

I will give only one example of theory straying into the other magisterium. There are many, many others. Because it is in the core of my discipline, it is something I can discuss with knowledge.

In the second volume of his History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault makes a number of empirically testable assertions about classical antiquity. Reading his book, it is clear that his Latin is weak to non-existent, and that he makes comments about the substantive content of Roman law that indicate that (a) he doesn’t know it and (b) when he does know it, he misunderstands it. This is well nigh inexcusable; there are many good translations of various books of Roman law, including separate translations of Gaius’s Institutes and Justinian’s Corpus Juris Civilis. Some of these translations are by Peter Birks, the doyen of unjust enrichment/restitution and one of Legal Eagle’s intellectual inspirations.

Because Gaius was writing when the empire was pagan, it is possible to compare what Roman law looked like in the first and second century AD with what Justinian wanted delivered in his Christian empire. By comparing the two texts, one can also see what the Christians deliberately changed or removed, which is a fascinating study in itself. Foucault seems to be unaware of any of this. Roman law scholars have often complained to their classicist colleagues about the use of Foucault in the classics curriculum (I have been witness to a couple of these stoushes), to be rebuffed with assertions about the supremacy of theory and theoretical approaches. Lawyers (law being one of the social sciences) now shrug their shoulders and accept that to the extent that classicists give primacy to theory, they are rendering themselves irrelevant.

In my case — and this at one of the world’s great universities — I had it asserted to me during my MPhil Viva that philosophers don’t have to prove anything, because they are philosophers. Maybe this used to be the case, but were I a funder, I would hang out to dry any philosophy academic who asserted it in my presence. When philosophers make empirically testable assertions, then they have opened the door to the magisterium of science, and should expect to be swarmed over by quants with calculators.

5. As a corollary of my comment that there are too many universities producing too many people who know more and more about less and less until eventually they know everything about nothing, the humanities should abandon the requirement for a PhD for academic appointments. They should look instead for skilled and sympathetic teachers educated at the best universities (and we all know which ones they are; not all universities are created equal) who can convey to their students the value of being widely educated and literate, as well as teach competence in a foreign language. That anyone can leave a modern university not speaking a language other than English is an appalling indictment of the entire Anglophone tertiary education system and needs to be remedied forthwith.

6. Ideas that are politically effective and interesting as politics need to prove their intellectual worth in order to be admitted to the academy. Just because it is politically and economically important for queers and women and blacks to have equality before the law and equality of opportunity does not mean that there is any merit in the academic study of feminist, queer or black ‘theory’. There may be, but there should be a rebuttable presumption against the entry of political strategies into the academy as intellectual disciplines. Feminists often assert that the personal is political, but it does not follow that the political is academic. The distinction may be a fine one, but it is important to bear it in mind.

It's a bit late in the night for me to give the full attention to the interesting but lengthy articles. I will throw this in - just recently I saw an opposite complaint, that the techy-type majors are required to take English and other "soft" subjects yet liberal-type majors do not get any grounding in sciences. While a foundation in writing, history, etc. is valuable for any engineer, lawyer or medic, a foundation in how world works is equally valuable for... well, everyone.

If there was anything that depressed him more than his own cynicism, it was that quite often it still wasn't as cynical as real life.

Terry Pratchett, Guards! Guards!

Terry Pratchett, Guards! Guards!

- WampusCat

- Creature of the night

- Posts: 8464

- Joined: Fri Dec 02, 2005 2:36 pm

- Location: Where least expected

I loved the two years of Latin I took at around 14-15 years old. It had a lasting effect on my vocabulary and understanding of grammar. I still remember much of the Latin, but virtually none of the German I studied for two years after that.

In my case, I think it helped me learn to think, and it deepened my appreciation of ancient cultures.

Is it for every student? Probably not, but I do wish that it were available at all schools.

It does bother me, though, thar this author seems to consider Western civilization inherently superior.

In my case, I think it helped me learn to think, and it deepened my appreciation of ancient cultures.

Is it for every student? Probably not, but I do wish that it were available at all schools.

It does bother me, though, thar this author seems to consider Western civilization inherently superior.

Last edited by WampusCat on Thu Oct 28, 2010 3:34 am, edited 1 time in total.

Take my hand, my friend. We are here to walk one another home.

Avatar from Fractal_OpenArtGroup

Avatar from Fractal_OpenArtGroup

I tried to teach myself Latin from an old textbook I found at a flea market when I was a teen-- but my interest flagged when I discovered my understanding of English grammar terminology wasn't good enough for me decipher what the textbook was getting at.

I did take a short course in college called "Bio-Scientific Terminology" that explored the Latin and Greek word roots used in a lot of scientific nomenclature- and that's been quite helpful throughout my life in a variety of ways.

Learning a complete dead language seems like a waste of time to me, though, unless you have a particular interest in it.

I did take a short course in college called "Bio-Scientific Terminology" that explored the Latin and Greek word roots used in a lot of scientific nomenclature- and that's been quite helpful throughout my life in a variety of ways.

Learning a complete dead language seems like a waste of time to me, though, unless you have a particular interest in it.

- Túrin Turambar

- Posts: 6157

- Joined: Sat Dec 03, 2005 9:37 am

- Location: Melbourne, Victoria

The complaint isn't that valid for British or Australian universities, as technical degrees like science and engineering are composed purely of science and engineering subjects. In Queensland, at least, everyone is required to take English in Senior High School if they want to get an OP (Overall Position) score so that they can apply for university, but otherwise they can study what they like. And if they do go to university, then their education is entirely in their own hands and the hands of the faculty they study with.Frelga wrote:It's a bit late in the night for me to give the full attention to the interesting but lengthy articles. I will throw this in - just recently I saw an opposite complaint, that the techy-type majors are required to take English and other "soft" subjects yet liberal-type majors do not get any grounding in sciences. While a foundation in writing, history, etc. is valuable for any engineer, lawyer or medic, a foundation in how world works is equally valuable for... well, everyone.

Some people don't like the purely vocational approach to tertiary education and think that students should get a general education as well as training for a career. Melbourne University has actually started pushing that, by creating a series of general undergraduate degrees and considering only offering things like law and medicine to postgraduates. A similiar situation to how American universities work, in fact. It's something that I'm fundamentally opposed to, myself. Studying for a profession is already a big enough time and money commitment without being made to spend an extra year or two or three reading Plato or whatever. And while I approve of a general education, that's what Senior High School is for.

- Primula Baggins

- Living in hope

- Posts: 40005

- Joined: Mon Nov 21, 2005 1:43 am

- Location: Sailing the luminiferous aether

- Contact:

This is so true. I see examples every day in my RL friends of people who are highly intelligent, gifted in their areas of work, wonderful people, but stone ignorant about science and without knowing it.Frelga wrote:It's a bit late in the night for me to give the full attention to the interesting but lengthy articles. I will throw this in - just recently I saw an opposite complaint, that the techy-type majors are required to take English and other "soft" subjects yet liberal-type majors do not get any grounding in sciences. While a foundation in writing, history, etc. is valuable for any engineer, lawyer or medic, a foundation in how world works is equally valuable for... well, everyone.

I'm not sure there's a solution in the current climate, in which some people dismiss science as unimportant because their belief system excludes it, and some people dismiss it as unimportant because they're too sophisticated to bother their minds with anything so jejune.

And there's a huge mistrust of science: people don't understand what it even is, let alone how it works, and they dismiss what scientists say out of hand because they assume they're all corrupt for their own reasons, or that they're all corporate shills.

“There, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach.”

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

Both universities I have attended required science as part of their general education requirements My undergrad was more liberal arts focused, but still required two math or science classes of all Arts and Sciences majors. The university I attend now is a state school with a higher emphasis on science and engineering, and liberal arts majors are required to take 13 credits of science plus labs (that's about four classes). If liberal arts majors don't learn about the scientific method in higher education, I think it's because they don't want to, not because they don't have every available opportunity to do so.

"I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived." - HDT

I TA'd a chemistry class for non-majors. It was pretty shallow and I'm not sure how much of an understanding of science students got out of it - they were mostly just learning some really basic facts. No methodology, nothing of the thought process behind science. This has left me thinking that, while there is certainly a place for this type of class, the implementation is lacking. What a humanities or social sciences major needs is not a lesson in IUPAC nomenclature but a lesson in how science is done. But it's easier to teach IUPAC nomenclature.

I went to a small private university with an emphasis on liberal arts education. My dad complains I might as well have gone to engineering school because of all the science classes I took but the way the curriculum was structured, everything was divided in social sciences, humanities, and natural sciences (math and engineering were also in this category). You had to at the very least "cluster", or take three classes, in each of these areas. Of course, if all you did was cluster, that wouldn't even amount to an associate's degree so what a lot of people did was major in one, minor in the other, and cluster in the third. Or, and this was pretty common among humanities and social science students because the credit load on the majors was lighter, they'd double major in two separate areas. Except engineering majors only had to do one cluster because engineering was so bloody awful. And I both majored and minored in natural sciences. I thought I'd minor in philosophy but I just couldn't stop signing up for chemistry courses. Then I though I'd double but I wanted to finish in four years and have summers open for internships. So I went with a major in biochemistry and minor in chemistry and thus avoided some really scary chem labs.

I went to a small private university with an emphasis on liberal arts education. My dad complains I might as well have gone to engineering school because of all the science classes I took but the way the curriculum was structured, everything was divided in social sciences, humanities, and natural sciences (math and engineering were also in this category). You had to at the very least "cluster", or take three classes, in each of these areas. Of course, if all you did was cluster, that wouldn't even amount to an associate's degree so what a lot of people did was major in one, minor in the other, and cluster in the third. Or, and this was pretty common among humanities and social science students because the credit load on the majors was lighter, they'd double major in two separate areas. Except engineering majors only had to do one cluster because engineering was so bloody awful. And I both majored and minored in natural sciences. I thought I'd minor in philosophy but I just couldn't stop signing up for chemistry courses. Then I though I'd double but I wanted to finish in four years and have summers open for internships. So I went with a major in biochemistry and minor in chemistry and thus avoided some really scary chem labs.

When you can do nothing what can you do?

- Primula Baggins

- Living in hope

- Posts: 40005

- Joined: Mon Nov 21, 2005 1:43 am

- Location: Sailing the luminiferous aether

- Contact:

I majored in chem and got the credits for a minor in physics. But I didn't really get what science actually is (that it's not a mass of facts but a process and a way of thinking about the world) until I worked in a real research lab where the outcomes of our experiments weren't pre-printed in some lab manual. I learned to design experiments and how to set them up so I had the controls I needed to make the data meaningful. It was a lot of fun to crunch the numbers and see what we got, then design the next experiment so it would tell us more.

But I'm not sure how you would teach that, for real, in an undergraduate class intended for non–science majors.

But I'm not sure how you would teach that, for real, in an undergraduate class intended for non–science majors.

“There, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach.”

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

I took a math and science teaching course as part of a requirement for being an undergraduate TA. We focused a lot on how students can be taught both the material and the scientific method by doing experiments to learn a concept rather than just being lectured. There were examples of both primary and secondary classes where science was taught only in this way. Students would have a guide with questions and materials to test their hypotheses on a topic. The best subject in which to do this is physics, because it's hard to hurt yourself working with a small inclined plane.  It would be harder in a subject like chemistry, because it's too easy to for students to say, "Hey, I wonder what would happen if I put these two random chemicals together and heated them?" And boom, a new designer drug is made.

It would be harder in a subject like chemistry, because it's too easy to for students to say, "Hey, I wonder what would happen if I put these two random chemicals together and heated them?" And boom, a new designer drug is made.  But I imagine you could do something similar.

But I imagine you could do something similar.

The main problem with these teaching methods is that it takes a lot of patience and effort from the teacher. It's much more time-consuming to have students do an experiment to test Newton's Second Law than it is to just tell them F=ma. And, of course, it wouldn't work for every student. I have always been much more interested in theory than in practical research. I would much rather someone give me a lecture and then a problem set to do on my own. I don't even mind theoretically thinking up experiments, as long as I would never have to actually do it. So, like every teaching method, it is not perfect and not applicable to all students. I think the best way to teach science is a mix of knowledge and the scientific method. Teach students the basics of a topic, then have them design an experiment to answer a question about it. I do think that science courses geared towards non-science people are more and more moving towards this style of teaching.

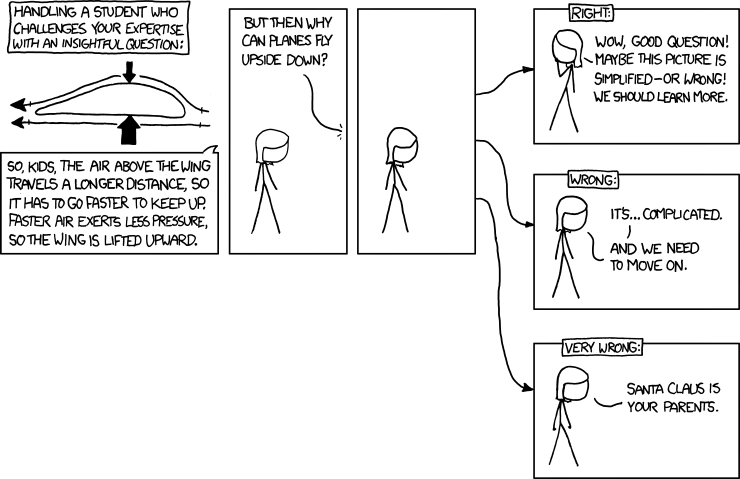

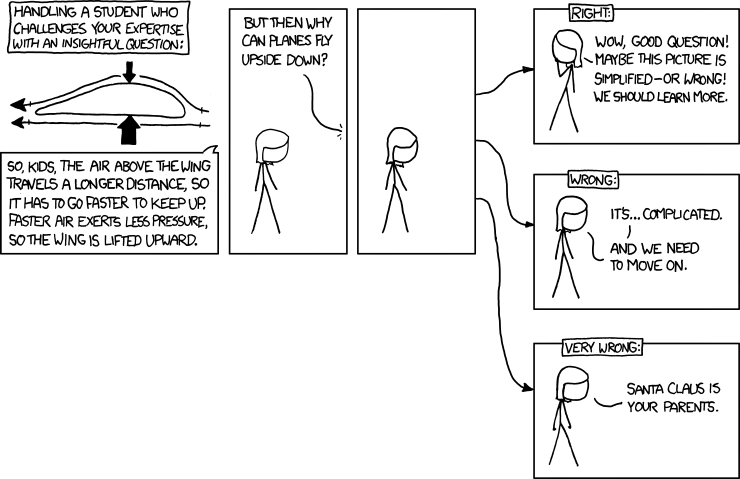

And, of course, we most importantly need to emphasize how important it is to 1) be skeptical of an idea until it is reinforced with hard data, and 2) question something if you don't understand why it is true. We have too many teachers and professors who just do this:

The main problem with these teaching methods is that it takes a lot of patience and effort from the teacher. It's much more time-consuming to have students do an experiment to test Newton's Second Law than it is to just tell them F=ma. And, of course, it wouldn't work for every student. I have always been much more interested in theory than in practical research. I would much rather someone give me a lecture and then a problem set to do on my own. I don't even mind theoretically thinking up experiments, as long as I would never have to actually do it. So, like every teaching method, it is not perfect and not applicable to all students. I think the best way to teach science is a mix of knowledge and the scientific method. Teach students the basics of a topic, then have them design an experiment to answer a question about it. I do think that science courses geared towards non-science people are more and more moving towards this style of teaching.

And, of course, we most importantly need to emphasize how important it is to 1) be skeptical of an idea until it is reinforced with hard data, and 2) question something if you don't understand why it is true. We have too many teachers and professors who just do this:

"I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived." - HDT

Absolutely agree. I was a biochemistry major and it wasn't until I got out into the "real world" of biotechnology that I understood ANYTHING about the scientific process. It just doesn't come across when it's canned. You'd think it would, but for me at least, it just didn't.But I didn't really get what science actually is (that it's not a mass of facts but a process and a way of thinking about the world) until I worked in a real research lab where the outcomes of our experiments weren't pre-printed in some lab manual. I learned to design experiments and how to set them up so I had the controls I needed to make the data meaningful. It was a lot of fun to crunch the numbers and see what we got, then design the next experiment so it would tell us more.

- Túrin Turambar

- Posts: 6157

- Joined: Sat Dec 03, 2005 9:37 am

- Location: Melbourne, Victoria

I agree, I just think that the appropriate place for that (and all other general education) is in high school.Primula Baggins wrote:This is so true. I see examples every day in my RL friends of people who are highly intelligent, gifted in their areas of work, wonderful people, but stone ignorant about science and without knowing it.Frelga wrote:It's a bit late in the night for me to give the full attention to the interesting but lengthy articles. I will throw this in - just recently I saw an opposite complaint, that the techy-type majors are required to take English and other "soft" subjects yet liberal-type majors do not get any grounding in sciences. While a foundation in writing, history, etc. is valuable for any engineer, lawyer or medic, a foundation in how world works is equally valuable for... well, everyone.

I'm not sure there's a solution in the current climate, in which some people dismiss science as unimportant because their belief system excludes it, and some people dismiss it as unimportant because they're too sophisticated to bother their minds with anything so jejune.It hurts both groups; it literally costs them money for one thing, even if it's something as trivial as paying $40 for half an ounce of skin cream that's supposed to "nourish" (dead) epidermal cells. It can also be something as nontrivial as ignoring a doctor's advice because alternative medicine sounds more pleasant than, say, surgery.

And there's a huge mistrust of science: people don't understand what it even is, let alone how it works, and they dismiss what scientists say out of hand because they assume they're all corrupt for their own reasons, or that they're all corporate shills.

I agree that there's also some things that you can't readily teach to 18- and 19-year-olds (let alone 14- and 15-year-olds) en masse, but must be built up to with both knowledge and experience. I sometimes idly wonder whether we shouldn't set a minimum age to begin non-technical tertiary education so that people spend a few years out of high school before they start University.

- Primula Baggins

- Living in hope

- Posts: 40005

- Joined: Mon Nov 21, 2005 1:43 am

- Location: Sailing the luminiferous aether

- Contact:

I disagree that science should be entirely relegated to high school. About all the science that is taught at the high school level is the kind of fact-memorization that doesn't produce any real understanding.

Yet science and math are the language the universe speaks to us; they're how we figure out physical reality. Surely it's at least as important to understand that as it is to understand, say, the history of philosophy or the underlying structure of classical drama. If that means studying it at an older age, so be it.

Yet science and math are the language the universe speaks to us; they're how we figure out physical reality. Surely it's at least as important to understand that as it is to understand, say, the history of philosophy or the underlying structure of classical drama. If that means studying it at an older age, so be it.

“There, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach.”

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

This is why undergrad science majors are highly encouraged to do research as undergrads. In fact, these days, if you want to go to grad school, you're pretty much not going to get in unless you have at least one summer internship behind you, and preferably a senior thesis project as well. Lab courses serve only to broaden a student's exposure, but once a student hits grad school or the real world he or she quickly finds that if s/she says "I did that once in <course name>," their colleague's response will be something along the lines of "Oh, okay, then you've never done this before. Let me walk you through it." But lab courses are also a good way to get spills, fires, and other fun mishaps out of your system.Ellienor wrote: Absolutely agree. I was a biochemistry major and it wasn't until I got out into the "real world" of biotechnology that I understood ANYTHING about the scientific process. It just doesn't come across when it's canned. You'd think it would, but for me at least, it just didn't.

Thinking about it, probably the most effective way to give students a taster of how science works is what elsha suggested. Give them a question and turn them loose on the equipment, with proper supervision of course. It doesn't have to just be inclined ramps and marbles either. I found those exercises in physics so boring I was turned off the subject altogether. The promise that these exercises would eventually morph into an understanding of ballistics that would give me the power to take over the world just didn't capture my young imagination the way "accidentally" setting a sodium fire in the chemistry lab did. If you give students the right chemicals, you won't necessarily end up with the next designer drug or, more likely, fumes, flames, an evacuated building and/or ER trip.

When you can do nothing what can you do?

- Túrin Turambar

- Posts: 6157

- Joined: Sat Dec 03, 2005 9:37 am

- Location: Melbourne, Victoria

I agree that the science curriculum in high schools could be significantly improved, both to give it a better focus on scientific thinking and a better connection with student's everyday lives. But I don't see why people who don't have an interest in science should be made to study it beyond junior high, just like I think that people who don't have an interest in classics or history or English shouldn't be forced to pursue them into voluntary education. I know that I would have resented the hell out of being forced to take classes in science or maths or english in university. I went there to study law. And I think that people who graduate from high school and go to university with the intention of studying engineering or law or medicine should be able to just get on with it and not have to take diversions into areas of study that they intentionally left behind. I have a very vocational view of higher learning.Primula Baggins wrote:I disagree that science should be entirely relegated to high school. About all the science that is taught at the high school level is the kind of fact-memorization that doesn't produce any real understanding.

Yet science and math are the language the universe speaks to us; they're how we figure out physical reality. Surely it's at least as important to understand that as it is to understand, say, the history of philosophy or the underlying structure of classical drama. If that means studying it at an older age, so be it.

This may be beyond the scope of this thread, but I have often been befuddled as to why schools don't place more emphasis on living practically in today's world.

There are so so many people out there who are totally ignorant of everday life situations and it seems to me that people as a whole would benefit from learning how to live in today's world more than they would benefit from lessons in higher math and sciences etc.

It is astounding to me how many intelligent people have no clue about nutrition, exercise, balancing check books, credit cards and many many other mundane things that would benefit them far more than E=MCsquared (I am ignorant as to how to make a power of two sign apparently).

Wouldn't it be better for society to find a more reasonable balance between practicality and higher learning?

There are so so many people out there who are totally ignorant of everday life situations and it seems to me that people as a whole would benefit from learning how to live in today's world more than they would benefit from lessons in higher math and sciences etc.

It is astounding to me how many intelligent people have no clue about nutrition, exercise, balancing check books, credit cards and many many other mundane things that would benefit them far more than E=MCsquared (I am ignorant as to how to make a power of two sign apparently).

Wouldn't it be better for society to find a more reasonable balance between practicality and higher learning?

- Primula Baggins

- Living in hope

- Posts: 40005

- Joined: Mon Nov 21, 2005 1:43 am

- Location: Sailing the luminiferous aether

- Contact:

Someone who studies no science after junior high is scientifically illiterate, in a world that increasingly poses complicated science-based questions to consumers and voters. A scientific illiterate can't make her own intelligent decisions and is vulnerable to demagogues, clever advertisers, and people with their own agendas, not to mention her own superstitions and prejudices.

In other words, I strongly disagree.

In other words, I strongly disagree.

“There, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach.”

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

So I learned basic health stuff in a HS class called "Health". They also covered fitness in PE but I dodged that. Balancing a check book and compounding interest was stuff we covered in math classes. I got a second, more in depth hit on nutrition in my Intro Bio II class my freshman year and a third hit in my biochem class junior year. Never got extra rounds of how to manage home finances; for some reason that didn't come up in calculus.Holbytla wrote: It is astounding to me how many intelligent people have no clue about nutrition, exercise, balancing check books, credit cards and many many other mundane things that would benefit them far more than E=MCsquared (I am ignorant as to how to make a power of two sign apparently).

What I'm getting at is this: there's no reason why practical stuff can't be mixed in to a science or math or whatever class. Often it is because that helps perk a student's interest. But what can and does happen is a student is in the class but not learning. It's not necessarily the teacher's fault either - I've been on both sides of the desk and I can tell you that the student does have a responsibility in the classroom and you can't and shouldn't dump all the praise and blame on the teacher. Some students just aren't motivated - believe me, I've been in that camp and I own that C+ just as surely as I own all my A's and B's.

When you can do nothing what can you do?